06 April 2022

Just because they are vaccinated, doesn’t mean they are confident

Written by Dr Heidi J Larson, Professor of Anthropology, Risk and Decision Science, and Founding Director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

While mandates, Covid “passports”, and health passes have, on the one hand, been a valuable lever to motivate compliance with needed outbreak control measures, they have had their consequences when it comes to public trust.

These restrictions have, for some, not only hardened sentiments towards vaccines, but towards government more broadly.

In addition, diverse groups of people who barely thought about vaccines before this pandemic, are now self-organising into globally-networked groups, and triggering public protests in multiple cities around the world. While these demonstrations around lockdowns, masking, vaccines, and overall government control measures were guised behind a mantra of “Freedom”, some of them turned violent.

Commenting on the New Zealand protests, one news report stated, “The mood of the gatherings has darkened over time and rhetoric from some protesters has included violent threats against politicians, scientists and journalists. Two schools in the area have shut for the week, citing ongoing harassment of students for wearing masks”.

Among the more unsuspected actors in these protests have been the truck drivers, whose Truckers Convoy choked the streets of Ottawa, Canada, for three weeks before the police moved in. Across the United States, other truckers united behind banners proclaiming, “Farmers & Truckers for Freedom”, and “Stop the mandates!”, and are using social media to plot their routes, plant their flags, and crowdfund their mission, with similar events erupting in Europe.

In a blog titled, “Covid Vaccination: the Last Mile”, physician and author Danielle Ofri wrote about a “unique obstinacy” around the vaccine, coupled with an unwillingness to even have a conversation. “What feels different this time around is the sense of deliberate manipulation and disinformation,” she said.

What is driving this?

Recent research from France is one of the few studies to shed light on – with evidence – the paradox of short-term vaccination gains, but longer-term trust consequences when it comes to imposing mandates and restrictions. In their important investigation, Ward and colleagues showed that while the introduction of the Covid health pass motivated a significant increase in uptake of the second dose of Covid vaccine – from 49% coverage with two doses in June 2021, to 89% by December – “…it has not reduced hesitancy itself…More importantly, the share of vaccinated people with doubts about the vaccine increased from 44% to 61% after the health pass was implemented”.[i]

The key point is that the health pass motivated those who may have been undecided, but still open to vaccination, but it hardened the views of those who were already more hesitant. As the French study identified, the early ones who were vaccinated reported feeling “relieved” after vaccination, whereas the ones who were more hesitant from the start, reported being “resentful” or even “angry” after vaccination.

Similar findings emerged from related research in the UK, which showed that while vaccine “passports” generally had wide support, among some segments that were more marginalised or already hesitant —primarily younger age groups, Black, or non-English speakers – their introduction made these groups even less willing to accept vaccination. Importantly, the study concluded that, “Although these groups comprise a relatively small proportion of the UK population, there are crucial issues that these perceptions among these groups cause: notably, that these groups tend to have lower baseline vaccination intent and they cluster geographically”.[ii]

In another UK study, ‘A “step too far” or “perfect sense”’, the authors identified six key themes among the responses: (1) a belief that mandates can be important when proportionate to the risk (i.e. for some occupations); (2) a feeling that mandates “undermine autonomy and choices”; (3) that governments are overstretching their legitimate power by imposing mandates; (4) that mandates could create vaccine “apartheid” (further alienating rather than engaging marginalised, more hesitant groups); (5) that framing and context matter; and lastly, (6) issues around the feasibility of mandates to implement.[iii]

The notion of mandates risking further polarisation of sentiment, with “apartheid”-like segregation of the unvaccinated, also featured in a Germany study. It concluded that “…reactance was stronger when a priori vaccination intentions were low” and, concerningly, “reactance increased intentions to take actions against the restriction”. This study also found that a mandate not only risked lowering Covid vaccine intentions, but also had an impact on other vaccines, in this case, “an unrelated chickenpox vaccination”.[iv]

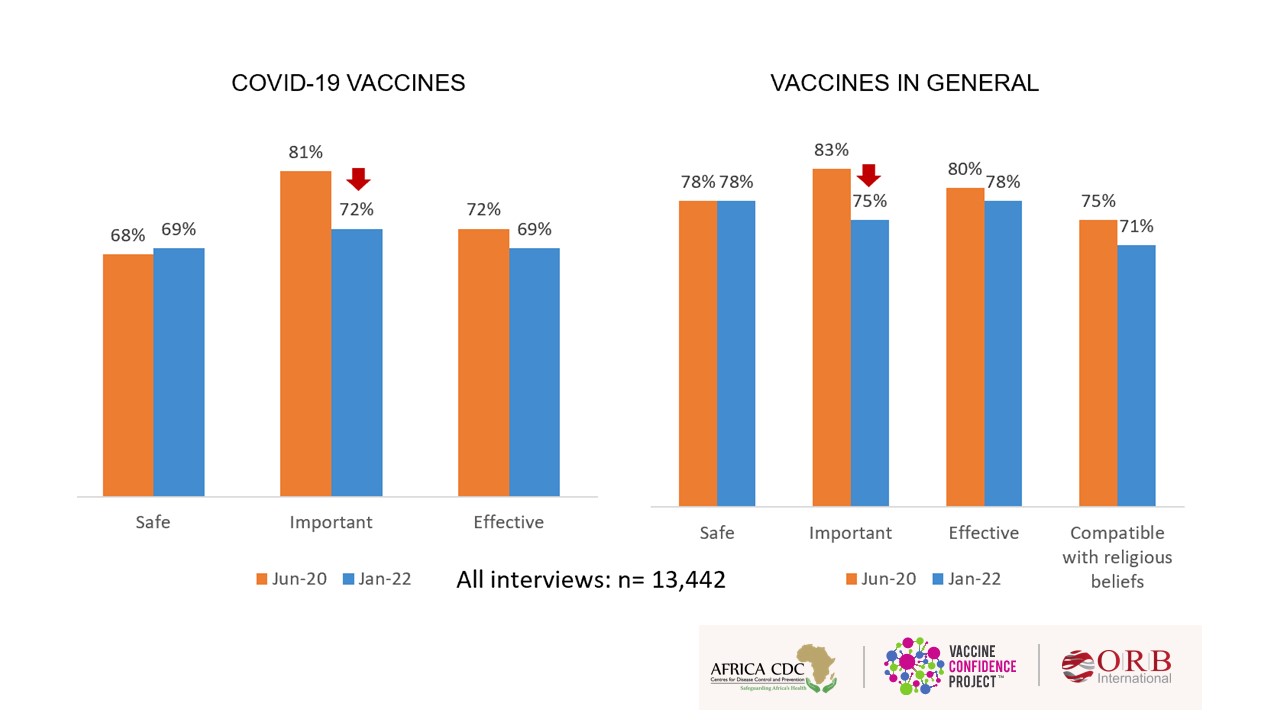

The knock-on effect of negative sentiments around Covid vaccines has emerged in other studies, such as the one undertaken with Africa CDC, which investigated Covid vaccine perceptions across 15 African countries. We found that perceptions of the importance and effectiveness of the vaccines declined between June 2020 and January 2022, with similar drops in confidence in the importance and effectiveness of vaccines in general.[v]

These are concerning trends.

The question is whether these sentiments will recover, and trust will slowly rebuild. It certainly won’t without a significant effort from all sides, but whether there is the will to overcome the “unique obstinacy” that has emerged out of Covid is yet to be seen.

As Jack Bratich poignantly stated in his article, “Give me liberty or give me Covid”[vi]: “Might this rupture open up a terrain of struggle that does not end in a typical post-crisis re-legitimation or restabilization? Indeed, we might be witnessing efforts at a more belligerent restoration. As Gramsci (1996) put it (and as plenty of commentators have recently re-invoked), this is a moment in which ‘the old is dying and the new cannot yet be born…”

[i] Ward JK, Gauna F, Gagneux-Brunon A, et al. (2022) The French health pass holds lessons for mandatory COVID-19 vaccination.

[ii] de Figueiredo A, Larson HJ, Reicher SD (2021) The potential impact of vaccine passports on inclination to accept COVID-19 vaccinations in the United Kingdom: Evidence from a large cross-sectional survey and modelling study.

[iii] Stead M, Ford A, Eadie D,et al. A “step too far” or “perfect sense”? A qualitative study of British adults’ views on mandating COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine passports.

[iv] Sprengholz P, Betsch C, Böhm R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19.

[v] Unpublished data from the Vaccine Confidence Project™

[vi] Jack Bratich (2021) ‘Give me liberty or give me Covid!’: Antilockdown protests as necropopulist downsurgency.

Truck image by Ottawa Graphics on Pixabay